The eroticism in art paintinglithium-ion battery in your phone might look like a solid chunk of energy-producing plastic at first glance, but if you were to bust it open and take a closer look, you'd see there's also some liquid inside. That's because most lithium-ion batteries are composed of multiple parts: two solid electrodes, separated by a polymer membrane infused with a liquid or gel electrolyte.

Now, MIT researchers believe they have taken the first steps forward in the development of all-solid-state lithium-ion batteries, according to new research published in Advanced Energy Materials. In non-nerd speak, that basically means batteries that could store more energy—meaning fewer trips to a power outlet.

SEE ALSO: Why your iPhone battery meter sometimes goes haywireThe team's report was co-authored by grad students Frank McGrogan and Tushar Swamy. They investigated the mechanics of lithium sulfides, which could someday replace the liquid as a more stable, solid form of electrolyte.

Switching out the liquid electrolytes for solids could be a big move. The all-solid batteries would likely be able to store more energy, "pound for pound," at the battery pack level than current lithium-ion packs. They'd also be much less unstable, since dendrites, which are metallic projections that sometimes grow through liquid electrolyte layers, would be less likely to occur.

The research team looked to test the sulfide's fracture toughness, which is essential to the material's role in a lithium-ion battery. If it's too brittle and can't handle the stresses of continual power cycling, it could crack and open up space for those same dendrites to form.

Original image has been replaced. Credit: Mashable

Original image has been replaced. Credit: Mashable The research faced one significant hurdle, however: the sulfide is so sensitive to room conditions it can't be experimented on in the open air. In order to test the material, the team placed the sulfide in a bath of mineral oil to prevent it from reacting before being measured for its mechanical properties. This was the first experiment to test for lithium sulfide's fracture properties.

After the test, the researchers concluded that the material does indeed crack under high stress conditions, "like a brittle piece of glass."

That said, the knowledge gained could allow the team to build new battery systems by "calculat[ing] how much stress the material can tolerate before it fractures,” according to MIT associate professor Krystyn Van Vliet, who contributed to the research.

Co-author Frank McGrogan agrees. This exact form of the sulfide won't be the solid material that makes it into the form of lithium-ion batteries we use today. But since the team can study its properties and design new battery systems around that knowledge, someday it could still have potential for use.

“You have to design around that knowledge,” he said.

(Editor: {typename type="name"/})

Nintendo Switch 2 preorder just days away, per leak

Nintendo Switch 2 preorder just days away, per leak

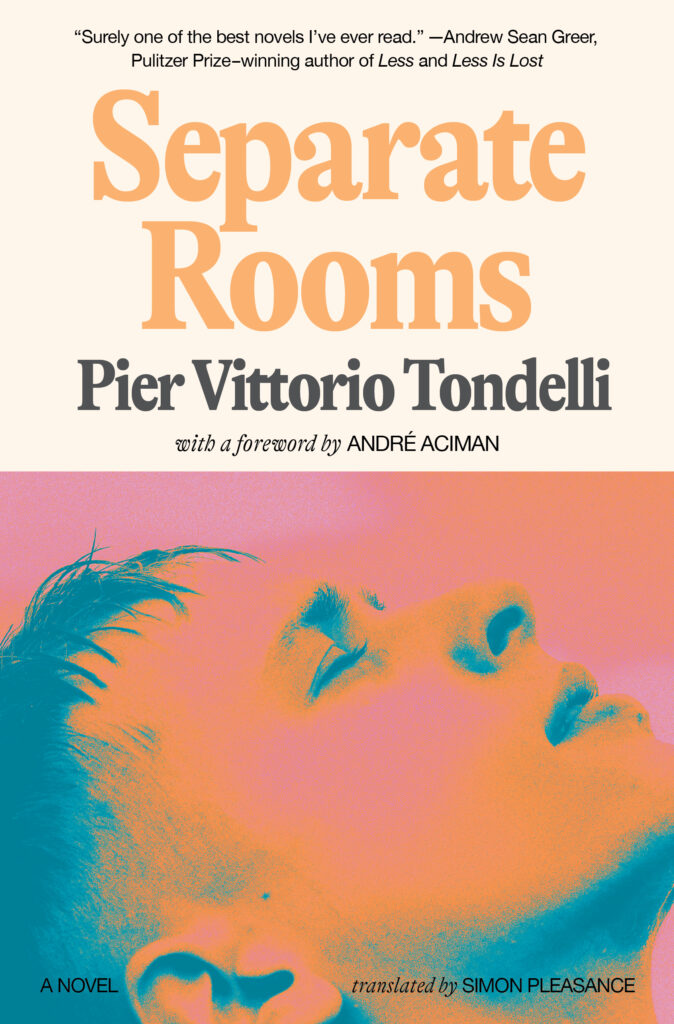

Cathedrals of Solitude: On Pier Vittorio Tondelli by Claudia Durastanti

Cathedrals of Solitude: On Pier Vittorio Tondelli by Claudia Durastanti

Today's Hurdle hints and answers for June 17, 2025

Today's Hurdle hints and answers for June 17, 2025

Today's Hurdle hints and answers for June 17, 2025

Today's Hurdle hints and answers for June 17, 2025

SpaceX's Starlink will provide free satellite internet to families in Texas school district

SpaceX's Starlink will provide free satellite internet to families in Texas school district

NASA's plan to return Mars rocks is in trouble. Could these 7 companies help?

As the Perseverance roverrumbled over Marsterrain scoping out rocks, seven companies spent the summe

...[Details]

As the Perseverance roverrumbled over Marsterrain scoping out rocks, seven companies spent the summe

...[Details]

NASA footage shows a moon landing like never before

It was a perfect moon landing. Although no easy feat, Firefly Aerospace's Blue Ghost lander descende

...[Details]

It was a perfect moon landing. Although no easy feat, Firefly Aerospace's Blue Ghost lander descende

...[Details]

Shop the early Prime Day deals on tablets from Apple, Lenovo, and more

SAVE $65:As of June 23, early Prime Day deals on tablets are trickling in. Catch the Amazon Fire HD

...[Details]

SAVE $65:As of June 23, early Prime Day deals on tablets are trickling in. Catch the Amazon Fire HD

...[Details]

Clever backyard water tank looks like a giant raindrop

Home rain catching is a pretty slick affair these days, no longer relegated to the realms of industr

...[Details]

Home rain catching is a pretty slick affair these days, no longer relegated to the realms of industr

...[Details]

Best smartphone deal: Get a refurbished Google Pixel 8 Pro for over $200 off at Woot

SAVE $230.01:As of June 24, get a refurbished Google Pixel 8 Pro for $389.99 at Woot, down from its

...[Details]

SAVE $230.01:As of June 24, get a refurbished Google Pixel 8 Pro for $389.99 at Woot, down from its

...[Details]

Mamelodi Sundowns vs. Borussia Dortmund 2025 livestream: Watch Club World Cup for free

TL;DR:Live stream Mamelodi Sundowns vs. Borussia Dortmund in the 2025 Club World Cup for free on DAZ

...[Details]

TL;DR:Live stream Mamelodi Sundowns vs. Borussia Dortmund in the 2025 Club World Cup for free on DAZ

...[Details]

Best power station deal: $400 off Bluetti AC180P

SAVE $400: As of June 23, get $400 off the Bluetti AC180P Portable Power Station — now at $499

...[Details]

SAVE $400: As of June 23, get $400 off the Bluetti AC180P Portable Power Station — now at $499

...[Details]

Today's Hurdle hints and answers for April 1, 2025

If you like playing daily word games like Wordle, then Hurdle is a great game to add to your routine

...[Details]

If you like playing daily word games like Wordle, then Hurdle is a great game to add to your routine

...[Details]

Best early Prime Day deal: Save 20% on the Anker Solix EverFrost electric cooler

SAVE $200:The Anker Solix EverFrost 2 electric cooler (40 liter) is on sale at Amazon for $699.99, d

...[Details]

SAVE $200:The Anker Solix EverFrost 2 electric cooler (40 liter) is on sale at Amazon for $699.99, d

...[Details]

Why Building a Gaming PC Right Now is a Bad Idea, Part 1: Expensive DDR4 Memory

Fluminense vs. Borussia Dortmund 2025 livestream: Watch Club World Cup for free

接受PR>=1、BR>=1,流量相当,内容相关类链接。